Join us for a candid conversation with Jukka Likitalo, Secretary General at Eucolait, as we delve into the dynamic landscape of European Dairy Trade Agreements. In this interview, we unravel the complexities and real-world impacts of these agreements, shedding light on the vital role they play in shaping the European dairy markets.

Despite their name, Free Trade Agreements (FTA’s) often come with nuances that extend beyond the day-to-day market dynamics. Jukka shares his insights, emphasising the lasting effects these agreements can have once concluded.

1. What is Eucolait, and how does it benefit its stakeholders?

For those of you who are not familiar with Eucolait: Eucolait is an organization that represents the interests of European companies engaged in the trade of dairy products. Eucolait serves as a platform for collaboration and communication among its members, who are involved in various aspects of the dairy trade, including import, export, and distribution.

The primary goals of Eucolait include: 1) Representing the interests of its members in discussions with European institutions and other stakeholders to influence policies related to the dairy trade, 2) Providing a platform for members to exchange information, share insights, and build networks within the dairy industry, 3) Enhancing market access for European dairy products in both domestic and international markets, 4) Monitoring and engaging with regulatory developments that impact the dairy trade.

2. What forms do Free Trade Agreements take in the Dairy sector?

In the context of these agreements, market access concessions for dairy typically manifest in two ways, which may sometimes be combined:

1) The gradual reduction or elimination of tariffs.

2) The application of tariff rate quotas.

The impact of FTAs is more pronounced when they involve countries where the dairy industry faces substantial tariff protection.

For example, the European Union (EU) exemplifies this scenario. Exporting to Europe is nearly impossible without a preferential agreement in place. Conversely, free trade agreements with countries like Singapore or Vietnam have had a limited impact on the dairy sector, as these nations already maintained low or zero tariffs prior to the agreements.

3. What are the top 10 countries that Europe exports to?

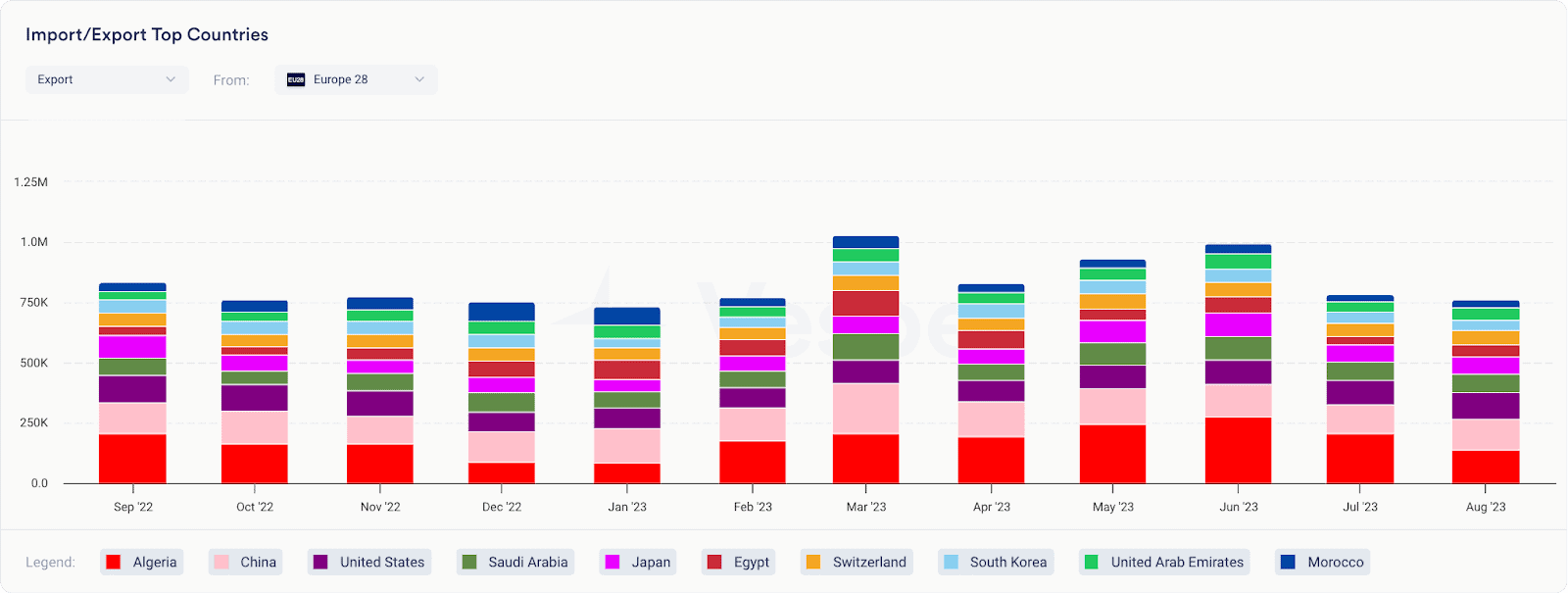

The Figure below highlights the top 10 exporting destinations for Europe, namely: Algeria, China, United States, Saudi Arabia, Japan, Switzerland, South Korea, United Arab Emirates, and Morocco.

Figure 1: Top 10 countries Europe 28 exports Milk Equivalent to in MT

For instance, Japan ranks fifth and South Korea eighth among these top countries. Despite having agreements in place with some of these nations, such as Algeria, the existence of a FTA may not be widely known, especially in cases like the deal with Algeria dating back to the early 2000s.

Notably, several countries in the Middle East, including Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, along with China and the United States, currently lack a FTA with Europe.

4. What is the impact of the trade agreement between Europe 28 and South Korea on Europe’s exports?

Europe 28 has an established trade agreement with South Korea, exemplifying a case where the outcome involves a combination of tariff rate quotas and gradual tariff reduction. This agreement, which has been in place for over a decade, featured low-volume duty-free tariff rate quotas, concurrently reducing import tariffs on various commodities. Notably, cheese and butter are pivotal in the context of South Korea.

The accompanying figure illustrates a notable upward trend in exports from Europe to Korea, as evident in Figure 2. While the data only extends to 2019, it is noteworthy that cheese exports to South Korea have increased significantly, rising from approximately 10,000 tons per year to an impressive 60,000 tons—a sixfold increase over the span of 10 years.

Figure 2: Cheese exports from Europe 28 to South-Korea in MT

Although part of this increase can be attributed to the growing demand in South Korea, the FTA has played a substantial role. The volume of metric tons traded freely varies based on the specifics of each negotiation and agreement. In the case of South Korea, duties are being gradually reduced over a 15-year period. In the coming years, complete duty-free access is anticipated for items like cheese.

Currently, there exists a small duty-free quota of around 5,000 tons, beyond which duties have been progressively reduced and are already relatively low at this stage. This nuanced approach to tariff reduction contributes to the ongoing positive trajectory of European exports to South Korea.

5. How has the trade agreement with Canada impacted European dairy exports, especially considering Canada’s historically protected dairy market?

A relatively recent agreement, dating back to 2017, involves a noteworthy trade partnership between Europe and Canada. This agreement holds particular significance due to Canada’s reputation as one of the most heavily protected dairy markets globally. The allocated cheese quota under the EU-Canada agreement represents a substantial portion of the market access available.

Over the past 5 to 6 years, European cheese exports to Canada have approximately doubled, surging from 14,000 to 26,000 tons. Despite the growth, it’s crucial to note the limited scope of market access concessions granted by Canada. The agreement entails a gradually increasing quota over approximately 10 years, after which no additional market access concessions are provided.

While the terms are somewhat restricted in the case of Canada, the impact on European dairy exports is evident, offering a valuable albeit limited opportunity within Canada’s protected dairy market.

6. What is the potential impact of future Free Trade Agreements in Southeast Asia, considering the current trade landscape?

The effectiveness of a new FTA is often maximised when implemented in a country with a heavily protected trade environment. However, a notable absence from the EU FTA list includes several Southeast Asian markets like Indonesia and the Philippines, where negotiations are actively ongoing.

In these regions, the potential FTAs, if successfully concluded, may offer limited benefits in terms of tariffs. This limitation arises because the tariffs imposed by these countries are already relatively low.

Nevertheless, establishing agreements is valuable not only for tariff reduction but also for addressing various other trade barriers, including technical and sanitary considerations. While the direct impact on tariffs may be limited, the broader implications of FTAs in Southeast Asia can contribute to overcoming diverse trade challenges, and fostering smoother trade relations in the future.

7. What is the current status of the Free Trade Agreement between Europe and New Zealand, and what potential impact does it carry?

The FTA between Europe and New Zealand presents a distinctive case of a trade agreement working in the opposite direction, favoring entry into Europe. As of Week 48, Europe has successfully completed the ratification process and approved the FTA, while New Zealand’s approval is still pending. It is anticipated that the deal could come into force sometime in the spring.

The road to establishing an FTA is lengthy, involving a minimum of two to three years of negotiations. Post-negotiation, Europe undergoes a process known as legal scrubbing, including translation into official languages, and ratification by the European Parliament. The entire journey from the start of negotiations to entry into force typically spans at least five years.

While the impact of the agreement with New Zealand is expected to be somewhat limited, it may lead to increased imports, especially during periods of significant divergence in commodity prices between the EU and New Zealand. However, the imports will be constrained by the agreed-upon quotas, especially for milk powders, with an initial quota of just 5,000 tons for Skimmed Milk Powder (SMP) and Whole Milk Powder (WMP) combined. Notably, both butter and powder quotas within the deal still incur tariffs, indicating they are not entirely duty-free.

Given the relatively small quotas and existing tariffs, significant market entry challenges persist, considering the saturated nature of the EU market. As a result, the expected surge in trade from New Zealand to the EU is not anticipated to be substantial

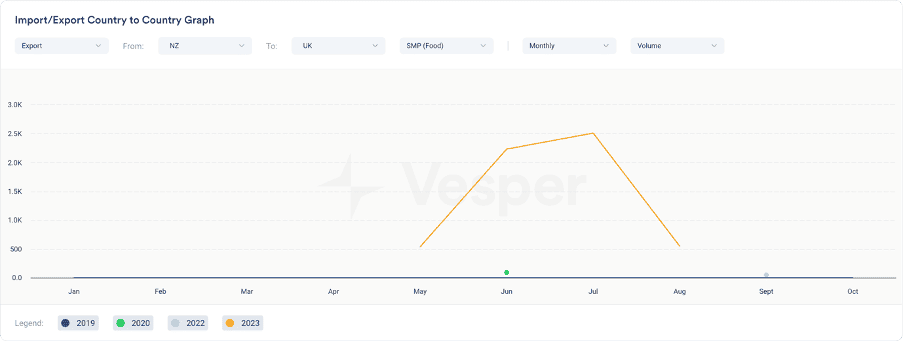

Conversely, a noteworthy FTA between New Zealand and the UK, in force since last May, has already seen increased trade activity, particularly in Skimmed Milk Powder, see Figure 3. This agreement provides for tariff elimination over three to five years, granting New Zealand progressively free access to the UK market. While the full impact is yet to be realised, expectations are set for increased trade between New Zealand and the UK in the coming years.

Figure 3: SMP (Food) exports from New Zealand to UK in MT

8. How is the current collaboration between the EU 27 and the UK structured, and what challenges have arisen in the aftermath of Brexit?

The collaboration between the EU 27 and the UK currently operates reasonably well, thanks to a comprehensive trade and cooperation agreement that averted a total disaster in the context of Brexit. The agreement was a last-minute resolution just before the transitional period, preventing significant disruptions.

However, the nature of this agreement is unusual. Typically, FTAs begin with high tariffs on both sides, aiming to reduce or eliminate them. In the case of the UK, given its prior membership in the EU, any outcome would be less favourable than the status quo. This unique dynamic characterised the negotiation as somewhat backward.

The impact of this agreement is evident at the end of 2020, with a notable decline in trade flows across all commodities groups, as illustrated in Figure 4. Despite maintaining duty-free trade with the UK, operational challenges stemming from customs procedures and veterinary checks have rendered some operations non-viable. Approximately 15% of pre-Brexit trade flows have been lost.

Figure 4: Milk Equivalent exports from Europe 27 to UK in MT

Additional factors contributing to these challenges include rules of origin requirements and the elimination of practices like using the UK as a hub—bringing EU 27 products into the UK and shipping them back to Europe is no longer a feasible strategy. The collaborative efforts between the EU 27 and the UK have mitigated some potential disruptions, but the altered trade landscape has introduced new complexities and limitations.

9. Could you provide insights into the recent discussions surrounding Halal certification, as a Non-Tariff Barrier to Trade?

The Halal certification issue has garnered attention as an example of non-tariff barriers to trade, potentially posing equal or greater harm than traditional tariffs. Algeria, for instance, implemented a new Halal certification, later revoked it, and then reinstated it. This certification process grants exclusive rights to an organisation in Paris, the Grand Mosque of Paris, to certify goods of European origin. The cumbersome and costly nature of this process has become a significant hassle for European exporters.

Despite the challenges posed by Halal certification requirements, the impact on trade flows has not been substantial so far. Notably, exports of Skimmed Milk Powder (SMP) from Europe 27 to Algeria have seen a significant increase in 2023, as depicted in Figure 5. While operators have managed to navigate the certification requirements, it remains a notable inconvenience and an additional cost likely to be passed on to Algerian consumers.

Figure 5: SMP (Food) exports from Europe 27 to Algeria in MT

It’s essential to highlight the distinction between Algeria’s Halal certification approach and those of the US and New Zealand. In Europe, businesses must work with one designated organisation, whereas in other countries like the US and New Zealand, entities can choose any Halal certification agency of their preference—an approach commonly adopted in various markets.

Critically, Algeria’s Halal certification process may raise questions about compliance with international trade rules. However, addressing this concern proves challenging, as Algeria is not a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO). Despite lacking WTO membership, Algeria does have an agreement with the EU, adding complexity to the issue of enforcing compliance with international trade standards.

10. What is the effect of the FTA, with South Korea, on protein powders?

The FTA between Europe and South Korea has notably impacted European exports, specifically in the realm of cheese and butter. Noteworthy is the considerable increase in exports of milk protein concentrates (MPC 85) to South Korea. Despite a year-to-date year-on-year decrease of 3.13% recorded in September 2023, MPC85 exports have more than doubled compared to 2019, as illustrated in Figure 6. This substantial increase can be attributed to the FTA, which has eliminated tariffs for the relevant product line (3504001010), driving this positive trend.

Figure 6: MPC85 exports from Europe 28 to South Korea in MT